'Not Looking

at the Hunter's Gun' 2009 (Video Still)

12

minute looped

HD Video

commissioned and curated by Katherine Daley-Yates

An

Artwork for Everybody and Nobody

by David Trigg

__________________________________

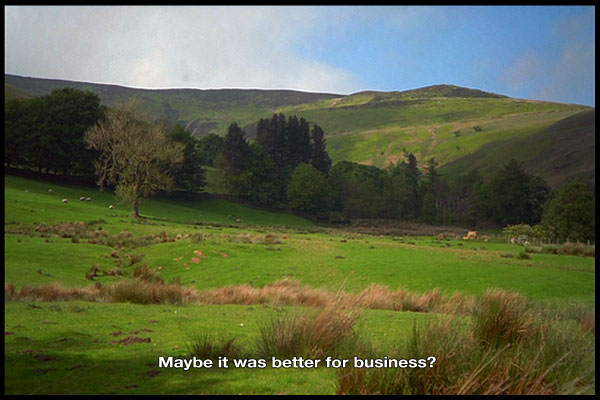

So what are we looking at? It’s a pertinent question, particularly

when confronted with an artwork by Ayling & Conroy. The artists

ask this question in their new film Not Looking at the Hunter’s

Gun, 2009, which presents a rambling, discursive tour of the artists’

collective mind. Filmed on location in the Derbyshire Dales, the visually

generous film comprises three lingering shots of glorious bucolic scenery.

Accompanying the images are a stream of disjointed, teasing subtitles

-- as if we were flipping through the artists’ notebooks. Works

in progress, glimpses into their thinking and brief insights into the

range of enquiries currently orbiting their practice are all referenced

by the fleeting texts. As the work unfolds, the deliberately tenuous

theme that loosely ties everything together is revealed to be the somewhat

broad notion of ‘landscape’.

It is worth remembering, that like so much of Britain’s countryside,

the heavily managed landscape of Derbyshire is a largely human construct.

This fact is echoed by some of the artists’ previous artworks

which are referenced in the film, such as their investigation into divergent

printed reproductions of Jeff Wall’s A Sudden Gust of Wind after

Hokusai, 1993 -- an artwork that Ayling & Conroy have never seen

in the flesh but only know from reproductions.

Wall’s digitally composited landscape, constructed from over one

hundred separate photographs, was inspired by a woodblock print from

Katsushika Hokusai’s popular series, 36 Views of Mount Fuji, 1830-33.

Like Wall’s photomontage, the landscapes of this popular nineteenth

century Japanese artist were themselves composed using a range of secondary

sources.

So then, the question remains: what are we looking at? Throughout their

fractured and open-ended projects Ayling & Conroy ask us to gauge

the role of mediation in the creation, diffusion and consumption of

cultural production; they challenge us to consider the legitimacy of

alternative ways of experiencing artworks.

Also referenced in the film is Gerhard Richter, for whom the very idea

of nature, or at least beauty in nature, is itself merely a human construct:

“We make our own nature, because we always see it in the way that

suits us culturally”, he has said. “When we look on mountains

as beautiful, although they’re nothing but stupid and obstructive

rock piles; or see that silly weed out there as a beautiful shrub, gently

waving in the breeze: these are just our own projections, which go far

beyond any practical, utilitarian values.” [1]

Ayling & Conroy thought they had Richter sussed; that is until they

stumbled across a newspaper interview which blew their preconceptions

out of the water: “Art should be serious, not a joke. I don’t

like to laugh about art”, he declared. Until that moment they

had always perceived a degree of humour in his artworks, but this revelation

caused them to question the validity of their subjective interpretations.

In response they created I, Gerhard, 2009, a project in which Richter’s

artworks and writings are studied for a year in an attempt to better

understand his practice. But how much study does it take to adequately

comprehend an artist’s oeuvre? Artists’ writings may help

us gain a deeper appreciation of their work, but they can also foster

narrower readings.

As Ayling & Conroy ask: “is there any value in additional

viewpoints, if our ideas differ from the actual meaning?” I, Gerhard

is well under way, but there are other ideas yet to be realised. A couple

of subtitles refer obliquely to Ayling & Conroy’s proposal

to place a sign in the hinterland landscape outside of Chongqing, a

densely populated city in China’s Sichuan Province. The sign,

or marker, will stand there until, eventually, the burgeoning city expands

to reach it. The work could manifest itself in a number of different

ways, or maybe not at all; remaining simply as an idea. Perhaps ideas

are sometimes all that is needed. The majority of us would never experience

a project like this in situ, rather it would be mediated via documentation,

word of mouth and written accounts (such as this one). Ayling &

Conroy are asking more questions: is anything more required than ideas?

Can an artwork successfully exist in the imagination alone?

The film’s apparent wildcard is Friedrich Nietzsche. Although

seemingly unrelated to any of the artists’ other concerns, it

is actually the philosopher’s relationship to landscape that fascinates

Ayling & Conroy. Nietzsche often found inspiration while walking

in nature; in 1881 an encounter with a towering pyramidal rock on the

shore of Switzerland’s Lake Silvaplana helped crystallize his

understanding of the concept of eternal recurrence -- the ancient idea

that the universe is incessantly recurring, infinitely replicating itself

from eternity past to eternity future -- which was the central theme

of his celebrated philosophical novel ‘Thus Spoke Zarathustra:

A Book for Everyone and Nobody’.

Nietzsche’s subtitle reflects the highly personal nature of his

work and the myriad of subjective readings he anticipated: anyone is

free to read the book, but who besides the author can truly understand

it? Similarly, Ayling & Conroy’s work is highly personal --

reflecting their own interests and preoccupations -- yet at the same

time they provide a seductive visual hit we can all understand and appreciate.

But how many of us have actually read Nietzsche? Ayling & Conroy

certainly haven’t -- a fact they readily admit, thus deliberately

undermining the authority of their transitory statements. Placing question

marks over certain assertions immediately raises doubts about others:

are there really 35 million people living in Chongqing? Did Jeff Wall

actually spend five months grafting together his photomontage? With

this deliberate undermining, Ayling & Conroy allude to Nietzsche’s

concept of perspectivism: that all ideation is relative, thus there

is no such thing as absolute truth -- but is that sentiment itself true?

In Nietzsche’s novel, Zarathustra describes aphorisms as ‘mountain

peaks’ or ‘summits’, suggesting vast amounts of underlying

thoughts and ideas to be sifted through before they can be adequately

understood. The same is true of Not Looking at the Hunter’s Gun

-- but how many of us will sift?

David Trigg

Notes.

[1] Hans-Ulrich Obrist, Ed., Gerhard Richter: The Daily Practice of

Painting, Thames and Hudson, London 1995, p.270

Epilogue

__________________________________

Not Looking at the Hunter’s Gun is a new film by Ayling &

Conroy, commissioned by Katherine Daley-Yates for the occasion of the

UWE MA Fine Art Degree Show 2009.

The development of the film was instigated through a series of conversations

that revolved around producing a new work that would respond to the

situation of curating on a Fine Art MA. The work also builds on the

commission that Ayling & Conroy produced for the previous project

Responses: Three Approaches to One Space (Spike Island, 2008).

The film is a continuation of Ayling and Conroy’s concern with

the production, experience and mediation of artwork, and builds on previous

work such as Sponsor the ICA by subtly agitating the context from within.

The meditative quality of the film and gentle probing questions, musings

and statements respond to the temporary didactic situation of the work.

Not Looking at the Hunter’s Gun also highlights the precarious

balance, between curatorial and artistic ownership. Although the artists

were invited to respond to a particular context by the commissioner,

they have regained partial control of the situation by curating a grouping

of work of their own choice. This process of negotiation demonstrates

the importance of the carefully developed relationship between artist

and commissioner.

Katherine Daley-Yates